Broken Wings

How do Canadians feel about "left wing" politicians, "right wing" politicians, and everything in between?

We’ve been calling politicians “left wing” and “right wing” since the French Revolution, with the genesis being where representatives sat in the National Assembly. To that end, these terms carry as much intrinsic meaning as if we labelled leaders “comfy seat” politicians or “sits near the bathroom” politicians.

But the terms have persisted and evolved, and are still widely used to describe leaders today. The problem is, a lot of voters don’t know what they mean, and those who do are sick of them.

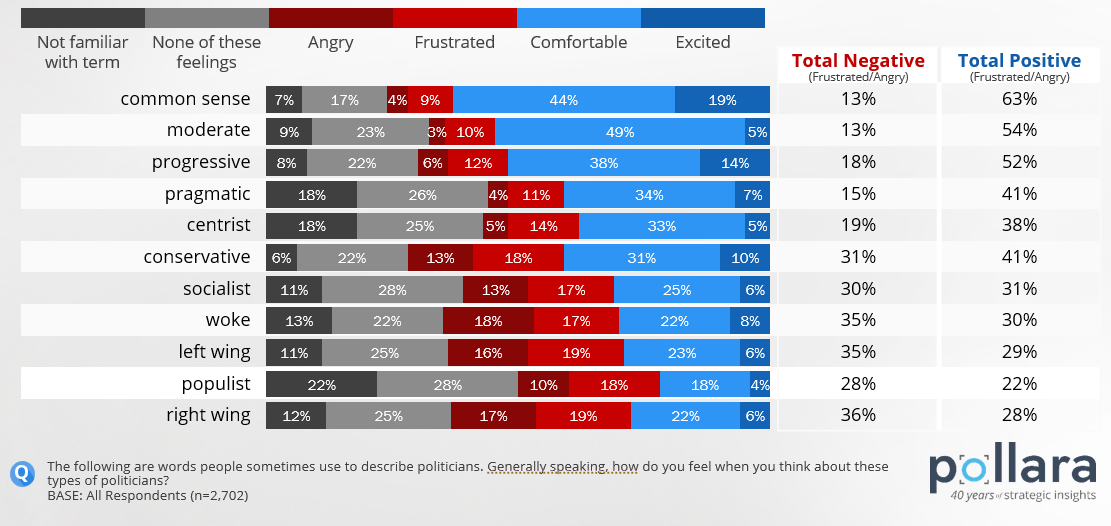

Pollara recently tested how Canadians feel about different political labels, and I present the findings, with terms sorted by net sentiment:

There’s a lot of grey and black on this graph, showing that many of these labels aren’t well understood, including left wing and right wing. Voters have a better sense of what it means to be “woke” than to be “left wing” or “right wing”.

This doesn’t surprise me, and it’s why I avoid asking voters to place themselves on the political spectrum in surveys. Not only do many people not understand “left” and “right”, but they rarely think in those terms. NDP voters who flocked to Mark Carney last election weren’t doing that because they wanted the country to move to the right. They were attracted to Carney’s CV, the stability he offered, and their confidence in him to handle an issue that isn’t really left/right.

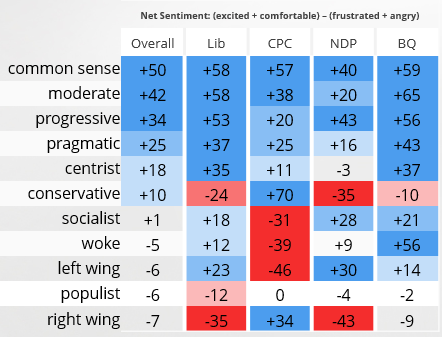

Our survey also finds more negativity than positivity towards both “left wing” and “right wing”. “Left wing” is the most hated term among Conservatives voters - even more so than “woke” or “socialist”. And “right wing” is the most hated term among Liberal and NDP voters - even more so than “conservative” or “populist”.

So what’s the lesson here? Well, the political spectrum is out. Being seen on a “wing” limits a party’s ability to grow beyond its base. And while “centrist” does a bit better, it’s one of the least understood and least exciting terms we tested. There’s no point in parties trying to define themselves using these labels.

What should they use instead? “Common sense” is the undisputed winner. This is branding most famously used by Mike Harris, and “common sense Conservatives” is one of the many 3-word slogans routinely trotted out by Poilievre1. I can’t recall anyone on the left ever using that branding, but as this data shows, it resonates nearly as much there as on the right. It’s actually the term that excites Liberal voters the most. I’d love to see a party brand itself as “common sense progressives”.

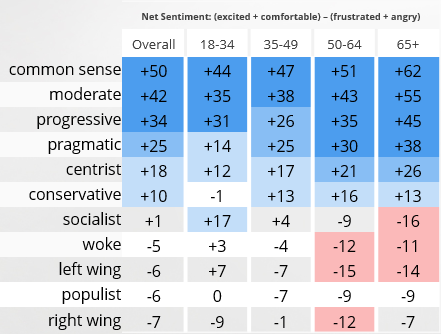

The other thing that stands out in this data is young people. That’s not surprising since young people stand out in most political data sets these days, because they’re experiencing politics so differently from everyone else. In the last election, Gen Z got more election news from TikTok than from TV newscasts - that’s going to have an impact on how they look at politics.

Young people are more comfortable with “left wing”, “woke”, and “socialist” politicians than older voters are. Of all the terms we tested, the age effect on socialism is the most stark: 10% of 18-to-34 year olds are excited about socialist politicians, 28% are comfortable, 14% are frustrated, and 8% are angry. Compare that to seniors, where just 1% are excited about socialists vs. 19% who are angry.

So what’s going on here? We’ve got some fresh polling coming to this Substack next week that has the Conservatives leading by 3 points among 18-to-34 year olds. Even though the small-c conservative brand elicits net negative sentiment with that same group. How is it that these left-wing woke socialists are flocking to the Conservatives?

The answer is what I talked about earlier - voters don’t think about “left” and “right”. Young people are the most open to “populists” and the least excited about “moderate”, “pragmatic”, or “centrist” leaders. Those terms convey stability to older voters, but young people aren’t after stability, they want to turn the system upside down. Who cares if it’s a “socialist”, a “populist”, or a “sits near the bathroom” politician offering that?

Full poll results can be found here.

And more commentary on the “populism paradox” by my colleague Andre Turcotte can be found here.

“Common sense Conservatives”, “Axe the tax”, “Build the homes”, “Do the dew”

Interesting piece. One thing that stands out is that this looks less like a messaging failure and more like a mapping failure. If left/right no longer reliably cues meaning or identity for voters, that suggests those axes no longer align with how political competition is actually organized. The language is breaking because the structure underneath has shifted.

Observation: only those in upper income brackets have rhe luxury of voting for the party closest to their political perspective.

The rest vote with their wallet, based on political spin they believe based on advertising.